prisonist.org

Release Day: June 5, 2007. My Last Day in a Federal Prison, by Jeff Grant. An Excerpt from My Unpublished Book, “Last Stop Babylon”.

June 5, 2007. Release Day. I am humbled and grateful to God, and to my family, friends, fellows, Fellow Travelers, colleagues and clients – and my wonderful wife Lynn – for the second chance I have been given over the past 15 years. – Jeff Grant

_________________________

As I’m sure I’ve said once or twice already, the hardest parts of a prison bid are at the beginning and at the end. My bid is finally at its end.

My case had been situated in the Southern District of New York; I appeared and was sentenced on Pearl Street in Manhattan. But even before I was arrested, my family had moved to Connecticut, where we lived for over four years now. Complicating things further was the fact that my wife and I were separated, so I really had no home in either Connecticut or New York. Without a home, I would not be eligible for early release for good behavior (three and a half months) nor would I be eligible to go to a halfway house (five weeks). The math was simple: if I didn’t find a home soon, then I would have to stay in prison the entire eighteen-month term of my sentence.

I started making calls. My best shot was with my best friend Peter. Peter had been in A.A. with me since the beginning, was like an uncle to my kids; I was like an uncle to his daughter Jamie. Peter had my power of attorney; certainly he’d let me stay with him for six or eight months. That would be long enough to satisfy probation that I was being released to someone, and somewhere, secure. After Peter had split up with his wife a few years prior, I had furnished his new apartment with the basement furniture from our old place in Rye. So in essence I was be asking him if I could move in to be reunited with my old stuff. That evening, after waiting the usual one-hour for one of the four phones outside the guard’s office in the unit, I actually got Peter on the phone. Even though Peter was a Harvard graduate, I still had to meticulously walk him through the steps of why I wanted and needed him to put me up for the next year or so. He had a three-bedroom apartment, he had an extra bedroom, and I would pay rent. I expected him to wrap his arms around me and welcome me home. Well, of course that didn’t happen. Instead, he told me that he’d get back to me.

Peter made me wait almost three excruciating months for his reply; months where I could have, and should have, pursued other options. In the end, he turned me down; he told me it wasn’t convenient because his girlfriend sometimes liked to come over and play scrabble with him in the evenings. It was never really made clear to me this was really an excuse for some other reason he didn’t want to discuss. But I did learn a huge lesson. There was no way I could ever again expect the type of treatment I received when I was a big shot lawyer.

I suppose I can’t really blame Peter. He took things very hard. We met in our AA home group in Greenwich. He had six months more time than I did, but we were always traveling different paths. He was Italian, and had spent most of his entire adult life living and working in the Far East. Like the rest of us, he suffered big losses for his drinking and drugging. But he just couldn’t accept any of it; after all, he was a Harvard man, the one who was supposed to have it, and do it, all. But there I was giving him advice for almost the entire four years before I went to prison. It should have been a case study in how you can’t change anybody. Three days before I left for Allenwood, I found Peter curled up in a fetal position in his bedroom. I’d been around a lot of guys who needed help by this point, and I knew that just another AA meeting wasn’t going to do it. I roused Peter sufficiently for us to call his psychiatrist, who had been giving him a steady supply of Klonopin to make it through the day. With his doctor’s instructions, I called my alma mater, Silver Hill Hospital, and arranged for Peter to check in. So three days before I self-surrendered to Federal prison, I drove Peter up to the beautiful rolling hills of New Canaan, Connecticut where we spent the day in admissions.

Now I was in a panic. I had only a few weeks remaining before I’d pass the point of no return and be denied good behavior time and halfway house. My friend Nina, who lived in New Canaan (coincidentally only a mile or two from Silver Hill), occasionally rented out her guestroom to alcoholics. But, as far as I knew, she only did so to women. Nina was lovely, older, lived alone, and I always thought she had kind of a crush on me. That was a big card to play. The most important thing was to get Nina onto my approved phone and visitors list so we could discuss things.

Before I could call anybody from the phones outside the guards’ office in the unit, I had to fill out and submit a contact list to my counselor. I was only allowed to have twenty names and phone numbers on the list at any time, but I could rotate names on and off the list as many times as I wanted. But there was no way to gauge how long it would take to get the names approved. So, I was always juggling, taking names off and putting others on so that I could speak to people I needed to call. Some names were permanent fixtures on my list, like my kids, my sister Andrea, Lynn, Peter, George (my AA sponsor) and Dr. Delvecchio (my psychiatrist). Having people on my contact list was one thing, getting access to a phone was another? Sometimes the line to make a single fifteen-minute call could be as long as two hours. Of course, there were always much shorter lines at the end of the month because everyone had used up their 300-minute monthly time allocations by then; this was not exactly a culture in which people were willing to delay gratification.

I called Nina and she was thrilled to hear from me. I practically could hear her gushing over the phone. I explained my situation to her and, unlike Peter she didn’t hesitate at all. I explained that a probation officer would come interview her and inspect her home. No problem, Nina was a pro that had been through plenty. She wanted to know if I needed to be picked up at prison. She was game for anything. I told her I’d be in touch. The problem now averted, I had to go put my paperwork through and apply for halfway house approval. There is only one Federal Bureau of Prisons approved halfway house in the State of Connecticut. It’s in the Westside ghetto of the city, near Asylum & Sigorney Streets (pronounced Sig-a-knee to Hartfordites), and it housed releasees from both the Federal and the Connecticut Department of Corrections systems. I was soon to find out that this was not a good thing. Nor would much be about my halfway house experience. But from my view right about then on the line to see my counselor, the halfway house was one step closer to home.

I called my sister Andrea to discuss some strategy for when I got out. Andrea was the only person, other than my kids, who stayed squarely on my side. But the ordeal of coming to visit me was too much for her too. She managed to visit me twice in those fourteen months, but she never really got comfortable with the entire situation. I explained to Andrea that I would be released on June 5th and then would spend up to eight weeks at Watkinson House in Hartford. If I got lucky, I could spend the last three weeks under home confinement at Nina’s place in New Canaan. I had no car, and wouldn’t be able to drive one while I was at the halfway house or under home confinement. But after that, a car would be very helpful since New Canaan is about fifteen miles from my kids, my friends and my AA home group that were all in Greenwich. She told me that she would work on it.

Days in prison are counted down to release, with the last day being your “wake up.” As the days grew closer to my release, I started my countdown in prison lingo: 30-and-a-wake-up, 29-and-a-wake-up. More and more of my “friends” left the compound for various reasons. Some were going off to have their own halfway house journey. Like my cellie, Les. He’d been locked up for eight years. In that time, his son had grown from two to ten years old. Les had only seen him twice. His ex-wife had been re-married to, and divorced from, a crystal meth dealer who beat her senseless while she was pregnant with his child. She’d given birth to the child, now about four, and was now pregnant with another. Les was considering going back to her once he reunited with his son who was now living outside Myrtle Beach. Others were Canadian citizens stuck in U.S. prisons on detainers, struggling to get the Canadian consulate to transfer them to the more lenient Canadian penal system. Hundreds others were undocumented or naturalized Latinos who were awaiting deportation proceedings. Allenwood was located in a region of about fifteen prisons served by a central immigration hearing office. Others got into fights and were escorted to the SHU, never to be heard from again.

Once Les left, I moved to his bunk and mine was filled by a crazy Russian kick-boxer who used to enforce for the mob. Or so he said, but I believed him. He had a very short fuse, and threatened me a few times in the last couple of months before I left prison. Thank God for Ricky, who seemed to know how to communicate with the guy? After I left, a corrupt accountant named Steve filled my bunk; he had no patience for the Russian at all. I guess the Russian had no patience for Steve either. One night the Russian had had enough of Steve, spun around and kicked him in the face, shattering his nose.

With about six days left (that’s 5-and-a-wake-up) things started to speed up. Tradition at Allenwood has it that the guy leaving throws a big dinner in the unit the night before he leaves. Any money left in an inmate’s commissary account is given to him by check as he is leaving the prison upon release. And, unless you are being transferred to another prison, it is an absolute sin if you leave with any prison clothing or gear whatsoever. It doesn’t matter what you paid for it, or how emotionally attached you became to any of it; you give away everything to your buddies before you leave. You go out the door with the clothes you are wearing, period. The guys on the inside need the stuff a lot more than anybody does after they leave; it’s kind of a code of honor thing. Of course, I saw more than once a guy give away all his stuff expecting to get released, only to have his discharge get held up for a few days. He had no clothes, sheets, blankets or towels. What a mess. But I was not one to buck tradition and I started to make arrangements to give away all of my prized possessions too.

There were big plans in the works for my going away party, and I’d been hoarding all sorts of stuff from the commissary to throw a big good bye for everyone. I had Spanish rice, assorted smoked fish in foil packets, packages of tortilla wraps, vegetable flakes, cookies, pretzels, potato chips. On 1-and-a-wake-up, I had about ten guys working the dining hall for all three meals, bringing back bags of smuggled food and vegetables, which we put on ice all day. I’d hired the best cookers in the unit. Immediately after dinner, I gave them all of the food that had been collected over the past few weeks, and smuggled all during the day. They brought it all back to their cubes and told us they would need ninety minutes. We spread the word that there would be a party at our cube at about 9:15, right after evening count.

Earlier that day, my name came up on the call out sheet with the code: “Mer-Go-Rnd”. It was the day I had to go around to each department on the compound and get them to sign-off that it was okay for me to be released, hence Merry-Go-Round. I received the check off list from my counselor in the unit, which was my first and last all-day, all-point compound pass in my stay at Allenwood. I returned to my unit with all the necessary signatures, and I was free to go. At 7:45, I went to my last pill line, and said good-bye to the staff and the nurse who gave me my medication every night. Back inside, I waited for count and prayed nothing would go wrong on my last night.

I had a lot of reason to think things could go wrong. Just the week before, I was standing by the phone waiting to make a call when two guys got into a fight. It was a particularly brutal fight, with blood flying everywhere. One of the guys lived in the next cube; his name was Flaco. Flaco may have been his nickname as there were a lot of Latino guys on the pound called Flaco (it means “skinny” in Spanish). The guards broke up the fight and took both Flaco and the other guy away to the SHU. SAS (prison FBI) came in, roped off the fight area, and investigated. When SAS was done, the blood spill team went to work. Inmates who need to make a lot of money and who presumably aren’t squeamish about infectious diseases man the blood spill team.

It turns out that a fight night was a very bad night to have a nosebleed. The air was very dry in these sealed units. So as I sometimes did, I had a little blood in my nose, wiped it on a tissue and threw it in the garbage of our cube. An hour later, the overhead lights came on with the speaker blasting,

“All feet on the floor, all feet on the floor.”

Five guards walked up and down the hallway screaming,

“Shirts off, hands out.”

They wanted to see if anybody else was involved in the Flaco fight. They got up to our cube and Les, Ricky and I were standing there, looking tired and innocent. That’s when one of the guards shined an ultraviolet flashlight into our garbage can and saw my bloody tissue. I think there were fewer alarms at Pearl Harbor than went off in the next minute or two.

There I was at midnight, about a week from my release, in a small office on the other side of the compound sitting across the table from two SIS officers who were looking pretty pissed off. They wanted to know exactly the “facts and circumstances” surrounding the bloody tissue in my garbage can. I answered every one of their questions to the best of my ability, which of course didn’t really matter a lick in that fun house. I told them that I had a bloody nose. They asked me if I could explain how I happened to get a bloody nose the same night as the fight. I told them that the air is dry every night. They asked me why would a fifty-year old man be in a fight with a couple of young Latinos? I told them that it was a hypothetical question, that I had a real bloody nose most nights. It went back and forth like this for a little while. Then they thanked me for my time and told me they’d be in touch.

It was a particularly balmy summer night as I walked back to my unit, and I stopped for a moment to gaze at the stars.

After count, guys started streaming into our cube for the going-away party. The cookers delivered over 100 fish and vegetable wraps. We had huge dishes of pretzels and potato chips, and over 50 chilled bottles of soda. Ricky surprised with a chocolate cheesecake he had commissioned by one of the unit bakers. It was excellent. Everybody in the unit was there: Bobby the disco king; the Canadians, Steve and Bill; Dennis, the new accountant who would soon get his face smashed by my new cellie the Russian arm breaker; Randy, the new Jewish kid who loved guns. We swapped stories and laughed, bonded by our situation. I knew that I had experienced something that most people would never see or understand. In a strange way I would miss this place. I gave out the last of my stuff and we all exchanged last good-byes. I snuggled off to my last night’s sleep in prison.

In a sea of nights in which I had laid endlessly awake, on this night I fell fast asleep.

Ricky walked me to the bench outside R&D at about 7:30 a.m., the same bench where I sat with Les only three months before. Les and I had about an hour of prison postscript before he had to leave. He gave me lots of notes on how I should handle myself while I was still on the compound and I told him what he could expect when he hit the street. So many things had changed in the eight years in the eight years Les had been behind bars. He had never seen an iPod or a Blackberry other than on television. Clinton was in the White House when he was arrested; now George Bush was soon to be on his way out. We talked about the twenty-two hour bus ride to his halfway house outside Myrtle Beach. This is where many ex-offenders are faced with their first tests: booze, drugs and women. Les had remained sober now for his entire prison bid. The only women he had seen up close in about six years were the female guards since he’d had no visitors. Les left without a whimper, just like all the others had. And now it was my turn. Ricky and I sat on that same bench talking, watching all the guys leaving their units heading for breakfast at the dining hall, morning pill line, and their early morning jobs, the same as they did every other day. But for me, this wasn’t any other day. We promised to stay in touch with each other, but in our hearts we both knew we wouldn’t.

The door to R&D swung open and the guard called out my name. Ricky and I gave each other a quick hug. I flung my little duffel over my shoulder, waved goodbye and stepped inside the door. I hadn’t been inside R&D since my first day at Allenwood and it looked nothing like I remembered it. That day seemed so long ago now, and such an ethereal part of my experience. There was now a little processing to do and some paperwork concerning my transfer to the halfway house. I had exactly five hours to drive to and check-in with Watkinson House in Hartford, Connecticut. They gave me a copy of my orders and a MapQuest printout. They also admonished me not to stop anywhere along the way because if I missed my check-in at the halfway house I would be sent back to prison for the balance of my sentence. I told them I understood. After about a half hour, two guards escorted out the front of R&D, out across the grassy courtyard that separated R&D and the visiting room from the front entrance of the prison. Once in the huge front entrance room, the one I had first entered with my friend Tom thirteen and a half months prior, the guards shook my hand, wished me good luck, and left. And that was that.

I walked out the front door of the prison alone, a little startled and not sure where my friends were. In order to be transferred to the halfway house, I had to submit for orders requesting specific people to transport me. I had asked Tom to drive me and he jumped at the chance. After all, he and his girlfriend Alexis had driven me up to prison, and both had visited me several times. He told me on the phone a few days before my release that he had a special surprise for waiting for me. I wasn’t sure if I could handle any more surprises, but I trusted Tom. I walked outside the doors and headed toward the parking lot, duffel over my shoulder wearing my last remaining prison uniform. On my feet was a brand new pair of Nike Air Force One’s that I had purchased at the commissary. There in the parking lot, standing next to Alexis’s Volvo station wagon, were Tom and Peter with the two biggest smiles I’d ever seen. Blasting on the stereo, with the windows rolled down, was Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love. The music grew louder as I walked towards the car.

Thirteen and a half months in prison and I finally got my boom box scene.

White Collar Week Tuesday Speaker Series – Craig Stanland, May 31, 2022, On Zoom, 7 pm ET, 6 pm CT, 5 pm MT, 4 pm PT

This is Your Invitation to Attend Our White Collar Week Tuesday Speaker Series

Please feel free to forward to friends, family members, colleagues and clients.

Craig Stanland

Author of Blank Canvas: How I Reinvented My Life After Prison

Tues., May 31, 2022, 7 pm ET, 6 pm CT, 5 pm MT, 4 pm PT

On Zoom

We are honored to have Craig Stanland as the next speaker in our White Collar Week Tuesday Speaker Series. Craig is a close friend who has been a member of our White Collar Support Group and ministry since 2013, and was a guest on our White Collar Week podcast. We sent copies of Craig’s book, Blank Canvas, to all of our support group members currently in prison – with rave reviews! Stay tuned for more information about upcoming speakers and events. – Jeff Grant

Craig is a powerful example of how to come back from the depths of professional and personal destruction and despair, survive and evolve in prison, and become a better, more fulfilled person living the life God intends for him. These lessons are universal – I’ve read Craig’s book several times and I highly recommend it for anyone navigating life’s difficulties. I guess that means everybody! Five stars!

Link to register for Craig’s talk on May 31st…

White Collar Support Group Blog: “Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There” by Fellow Traveler Bill Livolsi

Bill Livolsi is a Member of our White Collar Support Group that meets online on Zoom on Monday evenings. Bill has been a member of our ministry and support group since 2014. – Jeff

_________________________

I had the privilege of being topic leader at our May 16, 2020 White Collar Support Group meeting. This is text of that presentation:

We have a normal desire to solve our problems. And for my Fellow Travelers, once you add into the mix the anxiety, stress and the feelings of helplessness that accompany a criminal prosecution, the desire to repair the damage can be overwhelming, often to our detriment.

In many occupations being a take charge individual is how you advance your career. When issues arose, you dove in and you solved them. That’s how you proved your value to the organization, to your clients, to yourself.

My dad was a problem solver. Professionally he worked his way up from the mailroom, going to Wharton (undergrad) at night to be an international VP in the pharmaceutical business. My family, his friends, and his professional colleagues, looked to him for advice and solutions. I look to him still, even though he has been gone almost 13 years. He is the best man I have ever known. All I wanted, as an adult, was to be like my Father.

My willingness to take on the problems and challenges no one else wanted was very beneficial for my career too. I worked my way up the ladder to a CFO position by the latter part of the 1990’s. And as many of you know, this is where most of the problems, and difficult issues, organizations face end up. I was pretty good (and pretty lucky) at getting things right. It felt good to be the ‘go-to’ guy for my Company.

Unfortunately, there was a huge downside. My ‘fix it’ mentality also dominated my personal life and that didn’t work out so well.

“The skills that served you well in the advancement of your career aren’t necessarily the ones that will serve you now.” – Jeff Grant

In 2015 I was sentenced to 24 months incarceration after pleading guilty, in 2014, to one count of wire fraud and one count of conspiracy. I had been added as a defendant on a superseding indictment earlier that year. Many years prior, in 2007, I made the disastrous decision to inject myself into my spouse’s legal mess.

She and I met in early 2002 and became a couple a few months later. She was a private money manager. We married and had children. Our early years together were wonderful. I also invested significantly in the funds she managed, as did my family.

In 2004 we relocated to Oklahoma. At about the same time I left my CFO position in New York. I believed my finances and investments were in great shape, so I decided to retire early and spend time raising our two youngest children.

Life had other plans.

By 2006, things started to crumble. It started with strange calls to our home from one of her investors. Then, others starting showing up unannounced at our home. I had no idea why this was happening, and I was given several different explanations. There were civil lawsuits from investors including a court ordered freeze on her personal & business accounts.

Things were getting progressively worse into 2007. By late that year I was at my wits end. I was getting calls from family wanting an explanation. Instead of telling them the truth, that I didn’t know for sure what was going on and handing it off, I stayed in the middle. I passed along the information I was given. I assumed the information was accurate.

“An accurate understanding of reality is the essential foundation for any good outcome”. – Ray Dalio.

She let me know she secured another investor. This new investment would cover most of the redemptions that were due. This fact alone should have set off my alarm bells. It didn’t.

The on-going civil suits made it impossible for her to receive these funds, so I volunteered. I used my personal accounts to receive the investment on her behalf and to issue the pending redemptions.

There it was. Game Over. I just didn’t know it for another 6 years.

I have no doubt that you’re saying to yourself, how could you have been so stupid? Your actions were the textbook definition of a Ponzi scheme. What made you think this would solve your problem? Why didn’t you just walk away?

Good questions all.

I have done a lot of reading, research and reflection trying to get a better understanding of what was driving my decisions back then. There was overwhelming evidence that something was wrong, yet I was unmoved, even increasing my commitment. The passage of time brought clarity, and I understand why my decisions were so horrendously stupid and self-destructive.

- Greed. My priorities were horribly misplaced. Money and the acquisition of things took on an unhealthy importance.

- I Didn’t Grasp The Real Problem. The investment funds in question were nothing more than a Ponzi scheme (#1). The account freezes brought it all to a head.

- Sunk Cost. By 2007 I had invested 5 years in this relationship, and we had two children. I had vowed that this time around I would be a better husband, and a better father. Deep down I had to have realized that I did not know the full story, but I convinced myself that things would get better. They didn’t.

There’s more.

“The more invested we become in a decision, the more likely we are to rationalize or justify that decision, even if mounting evidence demonstrates it was the wrong one.”

“Escalation of commitment can happen in any aspect of our life. Think about the times when you over-invested in a failing project, stuck around in a miserable job, or when you’ve poured your heart and soul into a personal relationship that clearly wasn’t working.”

“Escalation is where people make errors because of their ego and their emotions. It’s not just a cold calculation of the loss of money or time. It’s the pain of threats to our sense of self. We’re afraid to admit a mistake and end up justifying a decision to ourselves.” (#2)

How did escalation manifest itself in my situation?

- Ego.

- My career experience convinced me I could solve this problem. I was supremely overconfident.

- Emotional Commitment.

- My family could be directly affected if this problem were not successfully resolved. I felt responsible to fix what was broken, but I was ashamed, and afraid, to talk with them.

- I would have been less emotionally attached to the outcome, and certainly could not have gotten directly involved, had the main actor been a stranger.

- I believed the survival of my marriage was dependent upon a successful outcome.

- I also believed, erroneously, that the future of my family relationships hinged me fixing this.

- Isolation.

- I disregarded the concerns of family and friends when they reached out to me.

- I ignored the important relationships that had been my reality checks in the past.

- By sequestering myself away from family and friends I had no one in whom I could confide and seek advice.

Did these emotional elements drive my decisions? Absolutely and unequivocally, yes. And it is clear to me these factors influenced my decisions far more than the money involved.

It wasn’t until I found my White Collar Support Group, and also served time in prison with other men like me, that I learned that emotional factors such as the ones I encountered are very common indeed. At one time or another almost all of us fell into the same trap, pouring more and more resources and ourselves into a bad decision, even when all the evidence was shouting ‘STOP’.

There are decades of research showing that the most powerful forces in our decision-making aren’t economic — they’re emotional. Had I done nothing in 2007, just sat there and let everything come crashing down, it’s almost a certainty I would not have ended up in prison.

It’s some consolation knowing that I’m not alone in the chronicles of disastrous decisions, and perhaps the only way for us to learn is by dealing with the consequences that follow them. I am hopeful that by sharing this I can help others avoid a similar fate.

Decision Making 101

- Is this really a problem?

- Breathe. There are very few problems in life that require immediate action.

- You likely don’t know as much about a situation as you think. Question what you think you know about any particular situation. There are things you know you don’t know (known unknowns), but there are things you don’t know you don’t know (unknown unknowns).

- Issues sometimes resolve themselves. Not suggesting you should put your head in the sand but recognize some issues self-correct.

- Why is this a problem? What is your desired outcome?

- Identify the right problem.

- Clearly define it and clearly define your goal(s).

- What is driving your urge/desire to fix/take control? Are you emotionally attached to the issue, or the outcome? It’s never wise to make a decision that is rooted emotions.

- What is the cause of the problem?

- Were events precipitated by your actions, or by the actions of others?

- Is this a problem you can realistically solve?

- If you didn’t cause the problem, it might be hard for you to resolve it without cooperation from others.

- You cannot control how others will perceive or react to your involvement.

- Do you need additional information or additional resources?

- Identify possible solutions. What could be:

- The easiest solution?

- The quickest solution?

- The best temporary solution?

- The best long-term solution?

- Set realistic parameters for success and failure so you know if/when to continue or abandon your effort.

- For example, what are the values and principles you don’t want to abandon or compromise?

- Vet your thinking with a knowledgeable and absolutely objective friend, colleague or mentor. Someone who will give you their unvarnished opinion. “An accurate understanding of reality is the essential foundation for any good outcome”.

Bill Livolsi is a Life Coach supporting the white collar justice community and a volunteer with Progressive Prison Ministries. He helps men and women facing prosecution for white collar and non-violent crimes navigate their journey – including rebuilding their lives after prison. He was prosecuted for a white collar crime and spent 13 months in Federal prison. Bill can be reached at whitecollarcoaching.com.

_______________________

- Review of the discovery documents with my defense attorney.

- Worklife With Adam Grant. How To Rethink A Bad Decision. March 29, 2021.

Entrepreneur: 3 Important Takeaways for Hiring Job-Seekers with Criminal Records, by Jeff Grant, Esq.

Jeff Grant is a member of our White Collar Support Group that meets online on Zoom on Monday evenings.

_________________________

Dear Friends,

I am pleased to share with you that an article that I authored titled 3 Important Takeaways for Hiring Job-Seekers with Criminal Records was recently published in Entrepreneur (see below).

As you know, overcoming the stigma and discrimination associated with having a conviction history is very near and dear to me, and I am personally invested in helping as many of the 70 million Americans like myself with conviction records secure the professional, educational, housing and other life opportunities we all need to thrive. The reality is that even long after serving our sentences, we are routinely denied gainful employment and thus the ability to meaningfully rebuild our lives. This article speaks to the immense scope of this issue and offers a simple, concrete solution on how we can begin to address it – by providing individuals who have completed their sentences with a clean slate.

A few months ago, I had the privilege of joining the Board of Directors of an organization called the Legal Action Center (LAC). For nearly 50 years, LAC has utilized a range of legal and policy strategies to fight discrimination, restore opportunities, and build health equity for individuals with arrest and conviction records, substance use disorders, and/or HIV/AIDS. Their proven track record of and ongoing commitment to helping tens of thousands of individuals overcome discriminatory barriers so they can support themselves, their families, and contribute to our shared communities is truly inspiring, and I am honored to partner with them in this critical work. The clean slate solution I mentioned above is just one of the many initiatives LAC is working hard to advance.

I cannot stress how important the efforts of organizations like LAC are to individuals like me – and our society at large. I do hope you’ll take a few moments to make a donation to support their mission – a gift of any size can help!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this message, and please do not hesitate to reach out with any questions you might have.

With deep gratitude,

Jeff

Donate to The Legal Action Center here…

_________________________

Reprinted from Entrepreneur.com, May 24, 2022

There are more than 70 million people in our country who have a conviction record. That translates to roughly one in every three Americans. The obstacles that those of us with records face are enormous. You would think that after we have completed our sentences, we should be able to move forward with our lives.

But the reality is that we face a multitude of often lifelong barriers that block us from essentials like steady jobs, educational opportunities, professional licenses, safe homes and more. In fact, the National Institute of Justice estimates 44,000 such barriers. These can severely limit or completely impede the ability of a person with a conviction history. They can’t effectively function in society and participate meaningfully in civic, economic and community life.

First takeaway: People with past convictions face an array of barriers to gainful employment

Due to widespread discrimination and stigma, individuals with conviction records are routinely blocked from employment opportunities. Even after having long ago completed their sentences. Whether a former CEO or trade worker, once an individual is branded with the scarlet letter of a conviction, it doesn’t matter who they were before. Many employers will quickly toss applications from formerly incarcerated individuals aside. The same for potential investors who will deny meetings with entrepreneurs who have records of conviction.

Predictably, the resulting economic insecurity, pain, shame and despair can be devastating. Not just for us as individuals, but for our families as well. People at every level of the workforce are impacted. But, systemic inequities and racially biased policing and prosecution in our country have yielded disproportionate rates of arrest, incarceration and conviction among low-income communities of color nationwide.

Second takeaway: There is a simple solution — provide people with a clean slate

Across the country, states are working to pass legislation that ensures individuals like me who have completed their sentences can have our records automatically cleared. There are many states where application-based sealing is currently an option. But this process is often incredibly burdensome and costly. Therefore preventing a significant number of people who would be eligible from actually having their records cleared. Efforts to automatically clear people’s records, also known as clean slate, help make it possible for all eligible individuals to start fresh. And, without having to navigate bureaucratic hurdles or spend money they don’t have.

When people have served their time and paid their debt to society, we deserve a second chance. A clean slate, erasure of the paralyzing, proverbial scarlet letter. Through automatic records clearance, this second chance can be fully realized — stable jobs, trade licenses, business ventures and secure homes would all once again be within our reach. Clean slate can give us the opportunity to truly move forward with our lives.

Third takeaway: Clean slate can help us all

Clean slate can give me and others with past conviction records a real chance at healing, justice and meaningful participation in the economy and communities we all share. It can also improve the well-being of entire families and communities. Individuals who want to work hard, support their families and contribute to their neighborhoods and local communities should be able to do so. We all know that children who grow up in poverty are far more likely to remain living in poverty throughout their lives — a brutal cycle known as intergenerational poverty.

Clean slate policies can help break this cycle. Furthermore, the benefit of clean slate policies for our economy at large cannot be overstated. The ACLU estimates that, nationally, excluding individuals with conviction histories from the workforce costs the economy between $78 billion and $87 billion in lost domestic product every year. With clean slate, employers looking to grow their businesses could tap into a huge pool of skilled workers. Without clean slate, we risk indefinitely locking away vast amounts of human potential. Amidst rising labor shortages, the great need for untapped talent is only increasing. Last, but certainly not least, clean slate can help begin to remedy the racial injustice pervading our country by breaking down the unjust barriers. Those that keep far too many Black and Brown Americans from reaching their full potential.

From social justice activists to Fortune 500 companies, clean slate has a diverse and wide array of supporters who believe in its immense potential. In New York, for example, the clean slate campaign has garnered support from top labor unions and business leaders like JPMorgan Chase. Also, faith leaders, survivors of crime, civil rights groups, law firms and health advocates. They all understand that not only is giving people a second chance the right thing to do, it is the smart thing to do. As they say, a rising tide raises all ships.

Jeff Grant serves as a private General Counsel and white collar attorney in New York, on authorized Federal matters, and as co-counsel with lawyers throughout the country. Reach him at GrantLaw.com.

Corporate Crime Reporter: Jeff Grant on Religious Ethics Versus Business Ethics

Jeff Grant is a white-collar defense attorney in Manhattan.

And he has an unusual back story.

More than twenty years ago, Grant lost his law license for dipping into client funds. He became addicted to prescription opioids and tried to kill himself. And he went to prison for more than a year for defrauding the Small Business Administration.

Since those traumas twenty years ago, Grant has undergone a transformation. He went to divinity school and became a minister. He started a ministry called Progressive Prison Ministries. He got his law license back and counsels people being prosecuted for white-collar crimes.

Every Monday, he holds a Zoom meeting with people around the country. It’s like AA for the white-collar community. (Grant himself has been to 10,000 AA meetings. In the early days of his recovery, he was going to three a day.)

In August of 2021, the New Yorker published a glowing profile of Grant’s work titled – “Life After White-Collar Crime – Every week, fallen executives come together, seeking sympathy and a second act,” by Evan Osnos.

“Almost everybody prosecuted for white-collar crime needs a lawyer to trust and someone who can empathize with them and understand the complexities of their problems,” Grant told Corporate Crime Reporter in an interview last month. “When they are being prosecuted for crime, they have many more problems than just their legal defense. They have bankruptcy issues, tax issues and maybe family issues. They also have spiritual and emotional issues. I try to take a look at the long game and help them forge a path from where they are, in a place of suffering, to a place in the future where they could hopefully have a happy, productive and happy life again. That’s a much larger view than a criminal defense lawyer might look at where they are simply trying to get the best sentence with the least amount of prison time.”

“I’m not saying that’s not important. That’s incredibly important. But the most important thing that I stress is that prison is not the worst thing that could happen to someone who is being prosecuted. Not having a comeback story is the worst thing that can happen. Thus far, the criminal justice system and the world in general has not shown a lot of compassion or empathy for people who have been prosecuted for white-collar crimes.”

“That’s changing as we have formed a community for a white-collar support group we started in 2016. We recently had our 300th meeting online on Zoom. We have been online since the very beginning. We are early adopters of the technology.”

“And we have over 500 members. We average about 40 people online every Monday night. There is a spiritual component. There is certainly an emotional component. But also we share a lot of information that is vital to successfully going through the process. And as a white-collar community, as we gain more information, we are best able to advocate for ourselves and defend ourselves. And we are no longer victims of the system.”

“There is a lot of information sharing. It’s run pretty much like an AA meeting. That’s the core of my sobriety. I have attended over 10,000 AA meetings at this point. On August 10, 2002, I will celebrate 20 years of sobriety.”

Is there a sense among some of your members that they too are victims of corporate crime, that the corporations in some cases have thrown them under the bus for higher ups in the corporation or the corporate criminal itself?

“It is such a complicated answer. The highest level answer I can give you is that everyone I have met who has been prosecuted for a white-collar crime has some kind of influence that has caused them to commit that crime. Whether it’s mental illness, substance abuse, childhood trauma, or social pressure, or business pressure to ride the line or cross over the line into some kind of unethical or criminal behavior.”

“These things generally do not happen in a vacuum. If you go deep enough into their history or their workplace, if you do real mitigation reports to learn the human side and the real intricacies of their business decisions, you find an amazingly rich story that humanizes the people accused.”

“Does corporate America throw its employees under the bus? The answer to that – it depends on the company. For the most part, large companies are represented by large law firms. They are trying to get either non prosecution or deferred prosecution agreements.”

“The corporations have huge resources they are able to apply. And typically when they are investigated, the question of whether any of the individuals of that corporation are going to be prosecuted is certainly up in the air. It’s part of the discussion. But historically, very few individuals are prosecuted up and down the line.”

“There are exceptions. Specific hedge fund traders have been prosecuted for insider trading. Sometimes they come to the attention of prosecutors because of a specific trade or series of trades. Sometimes prosecutors are trying to climb the ladder and get to superiors who they think are guilty of larger crimes or more institutional crimes.”

“It’s industry specific. Federal prosecutors have targeted healthcare companies over the last five years. In the future, it’s clear from the Attorney General’s recent comments in San Francisco that they are going to make individuals more accountable.”

“They are going to focus on new technologies where the law hasn’t quite caught up with the transactions. And they will focus on pandemic fraud prosecutions. SBA loans, PPI loans. I know a lot about that because I went to prison for an SBA loan. They are calculating that maybe as much as $200 billion or a million different loans were fraudulent in some ways. And those can be sizable companies. Those loans ranged from small loans to $10 million loans.”

“We are going to find that over the next five years, the floodgates will open in this area.”

You are saying that what leads these individuals to engage in white-collar crimes is a pathology – something triggered it?

“That’s fair.”

We interviewed Joel Balkan who has written that corporations can be pathological. Is there a sense among the group of individuals that you have dealt with about systemic pathology as opposed to individual pathology?

“Absolutely. You could go company by company and find that kind of systemic pathology. And you can find a generally toxic business environment that has historically honored the wrong things. For the most part, the public corporations operate quarter by quarter. And they do things that you might consider to be unethical, or push their people to do things in order to get quarterly results that might achieve it for a while but ultimately eats away at the fabric of that corporation and of the people who work at that corporation. There are many examples of where the corporate culture itself is so toxic that it has created an environment where for example its sales people are committing acts of bribery in violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.”

“What we are finding in the support group is that people have been asked to do things that they otherwise wouldn’t have done. Or it happens inch by inch so that they wake up one day and they find out they are over the line of ethics and legality. And they are not even sure how they wound up over the line other than the fact that their company has made them do it. They were making poor decisions. And second, the line keeps shifting as to what is ethical and legal.”

“A perfect example of that is insider trading. The last ten or fifteen years, the definition of insider trading keeps changing. How close to that line do you get to satisfy your employers? Almost every employer in the hedge fund industry wants their people to get as close to the line as possible. People in our support groups represent that experience.”

The Justice Department is heading back to the Yates memo calling for a renewed focus on individual wrongdoing in corporate crime prosecutors. Is this a good policy – to focus on individual wrongdoers within the corporation? Does it work in deterring crime?

“I don’t know if it deters crime. The benefits can be so disproportionate to what they perceive the risks to be. Example – you are a young person who has just come out of business school. And in your mind, you think you are going to make $30 million. How much deterrence would these prosecutions have if realistically you were told that one or two percent of the people who engage in this kind of criminal behavior are ever prosecuted?”

“You might view it as a minimal risk. The government doesn’t have the resources to go after enough people for there to be real deterrence.”

If not by criminal prosecution, how should the government deter wrongdoing?

“Let me answer your previous question – do I believe individuals should be prosecuted? The answer I have, both as a minister and as a lawyer, is that everybody should be held responsible for their behavior. Do I think that the prosecutor should understand all of the elements, including the personal elements? Yes. But anybody who overtly committed a crime should be prosecuted.”

“Should they go to jail? Jail is a draconian, inartful way of dealing with crime, rehabilitation and punishment. There are much better alternatives that work in other countries – Germany and Sweden for example. People can be held responsible for their behavior, but we would not be destroying people and grinding them up in the process and leaving them without the possibility of using their experience and education to better society.”

“There is a movement to do better.”

“As for deterrence, deterrence is a strange word. We have moved away from morals and ethics. The root is societal and cultural. Our colleges and universities were formed originally as seminaries and we taught morals and ethics. When they became professional schools and business schools, they traded religious ethics for what they call business ethics. Business ethics haven’t worked. It was a form of self-policing that created a culture that has undermined business. There has been push back recently. Now the business schools and law schools are teaching real courses in ethics and right and wrong, things you should have learned in kindergarten. But it took a lot to get there.”

How is religious ethics different from business ethics?

“Religious ethics is teaching a basic system of right and wrong, about what is healthy, unhealthy. It’s character building. You build your character and come closer to God.”

“Business ethics is about the health of the corporation and delivering value to shareholders. It’s a twisting of ethics to satisfy the needs of the business in the name of capitalism. But they disregard all the other stakeholders – including the planet, poor people, people who need resources but don’t have access to them. I’d like to think that in some ways we are moving back to a more humane and ethical understanding. But if you look at the number of billionaires and the disparity of wealth, we have a lot of work to do.”

A St. Francis style religious ethics would do away with most of the corporate state, wouldn’t it? It would oppose the military industrial complex – large parts of the economy. The healthcare industry would be transformed. Business ethics protects the corporate state while religious ethics would undermine it.

“I agree with that. To become the most powerful country in the world, we had to lose our religious underpinning.”

These 500 white-collar criminals who have gone through your program, how do they view the issue of corporate power and corporate crime?

“Everyone who goes to prison undergoes a transformation whether they know it or not or understand it or not. They come out different. Generally, the people in our white-collar group start off as people who are very material. Then somewhere in the process, they find their spirituality. Most of them commit themselves to a life of more spirituality and less materialism. You won’t find anybody who doesn’t acknowledge that they lived a hollow material life. And now what they want is a more meaningful and joyful life.”

“And it’s not all or nothing. Most people when they come out of prison, they are in survival mode. They are ex CFOs who are now driving for Doordash. Just survival is difficult. They have a new definition of success. The road back is through some spiritual component.”

[For the complete q/a format Interview with Jeff Grant, see 36 Corporate Crime Reporter 17(11), April 25, 2022, print edition only.]

White Collar Support Group Tuesday Speaker Series: Brian Cuban, Author of The Ambulance Chaser, Tues., May 10, 2022, 7 pm ET, 4 pm PT

We are honored to have Brian Cuban as the inaugural speaker in our new White Collar Support Group Tuesday Speaker Series. Brian is a friend who was a guest on our White Collar Week podcast. We sent copies of Brian’s new book, The Ambulance Chaser, to all of our support group members who are currently in prison – they loved it! Stay tuned for more information about upcoming speakers and events. – Jeff

_________________________

White Collar Support Group Tuesday Speaker Series

Brian Cuban Author of The Ambulance Chaser

Mon., May 10, 2022, 7 pm ET, 6 pm CT, 5 pm MT, 4 pm PT On Zoom

Open to Support Group Members by RSVP Only

Brian Cuban, the younger brother of Dallas Mavericks owner and entrepreneur Mark Cuban, is a Dallas-based attorney, author, and person in long-term recovery from alcohol and drug addiction. He is a graduate of Penn State University and the University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

His book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales of the Bar, Booze, Blow, and Redemption is an unflinching look at how addiction and other mental health issues destroyed his career as a once successful lawyer, and how he and others in the profession redefined their lives in recovery and found redemption.

Brian has spoken at colleges, universities, conferences, non-profits, and legal events across the United States and in Canada. His columns have appeared—and he has been quoted on these topics—online and in print newspapers around the world. He currently resides in Dallas, Texas with his wife and two cats.

RSVP for Zoom link here…

About The Ambulance Chaser:

After being accused of the murder of a high school classmate thirty years prior, lawyer Jason Feldman becomes a fugitive from justice to find the one person who can prove his innocence and save the life of his son.

Pittsburgh personal injury lawyer and part-time drug dealer Jason Feldman’s life goals are simple: date hot women, earn enough cash to score cocaine on a regular basis, and care for his dementia-ravaged father. That all changes when a long-lost childhood friend contacts him about the discovery of buried remains belonging to a high school classmate who went missing thirty years prior, and the fragile life Jason’s built over his troubled past is about to come crashing down. Soon, he’s on the run across Pittsburgh and beyond to find his old friend, while trying to figure out whom to trust among Ukrainian mobsters, vegan drug dealers, washed-up sports stars, an Israeli James Bond, and an ex-wife who happens to be the district attorney. The only way he’ll survive is if he overcomes his addictions so he can face his childhood demons.

Order Brian’s book, The Ambulance Chaser, here.

Podcast: Jeff Grant on the UnYielded Podcast with Bobbi Kahler, Mar. 30, 2022

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Jeff Grant is a member of our White Collar Support Group that meets online on Zoom on Monday evenings.

_________________________

Reprinted from bobbikahler.com, March 30, 2022

“Life is full of unexpected twists and turns. Also, Life can be fraught with numerous drawbacks. However, regardless of what happens, the most critical aspect is rising again. My guest for today has a life story that is worth discussing. After developing an addiction to prescription opioids and serving nearly fourteen months in federal prison (2006–07) for a white-collar crime committed in 2001 while working as a lawyer, he began his reentry by earning a Master of Divinity in Social Ethics from New York City’s Union Theological Seminary. After graduating from divinity school, he was invited to serve as Associate Minister and Director of Prison Ministries at an inner city church in Bridgeport, Connecticut. He later co-founded Progressive Prison Ministries, Inc., the world’s first ministry solely dedicated to white-collar crime. Jeff Grant, Private General Counsel/White Collar Attorney at GrantLaw, joins today’s episode to share the insights he has learned on his journey from prison to calling.”

Listen on Apple Podcasts

https://embed.podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/from-prison-to-calling/id1529949199?i=1000555708423

Show Notes

Jeff’s First Life – Jeff tells his journey of various twists and turns, none of which he could have predicted would result in such a great life.

Being Sober – Jeff discusses what he believes helped him stay sober when everything seemed to be collapsing around him. Isolation and Community – Jeff provides a comprehensive explanation about his saying, “Isolation damages us, and the answer is community.”

Comeback Story – Whatever the worst-case scenario occurs in our lives, we must have a story of redemption. Jeff explains how he assists someone is preparing to write their comeback story.

Jeff’s advice – Jeff delivers some suggestions for individuals who self-sabotage on how to move ahead.

Resources

Connect with Jeff: Jeffrey D. Grant, Esq., GrantLaw PLLC, GrantLaw.com, [email protected], 212-859-3512. LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/revjeffgrant Website: grantlaw.com

The New Yorker: Life After White Collar Crime, by Evan Osnos, Aug. 2021: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/08/30/life-after-white-collar-crime

Entrepreneur: 9 Things to Know When Hiring a White Collar Criminal Defense Lawyer, by Jeff Grant, Esq., Sept. 2021, https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/380464

Reuters: Why Lawyers in Trouble Shun Treatment — at the Risk of Disbarment, by Jenna Greene, November 2021, https://www.reuters.com/legal/legalindustry/why-lawyers-trouble-shun-treatment-risk-disbarment-2021-11-09/

#1 Most Viewed Insight on Bloomberg Law: Lawyers, Watch Out for These Five Signs of Addiction, by Jeff Grant, Oct. 2021, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/lawyers-watch-out-for-these-five-signs-of-addiction

Business Insider: A lawyer who went to prison for 9/11-related fraud just got his law license back, and became an ordained minister along the way, by Peter Coutu, July 2021: https://www.businessinsider.com/jeff-grant-lawyer-prison-minister-disbarred-911-law-license-reinstated-2021-7

Reuters: Jeff Grant ‘Let Go of the Outcome’: How this Felon Beat Addiction and Won Back his Law License, by Jenna Greene, May 2021: https://www.reuters.com/business/legal/i-let-go-outcome-how-this-felon-beat-addiction-won-back-his-law-license-2021-05-21/

American Bar Association Criminal Justice Magazine, “A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats: Progressive Diversion & Reentry,” by Jeff Grant and Chloe Coppola, Spring 2021: https://grantlaw.com/american-bar-association-criminal-justice-magazine-springp21-issues-a-rising-tide-lifts-all-boats-progressive-diversion-recovery-by-jeff-grant-chloe-coppola-2/

The Philadelphia Inquirer: Steal Money from the Feds? First, Meet Jeff Grant, an Ex-Con who Committed Loan Fraud, by Erin Arvedlund, Oct. 2020: https://www.inquirer.com/business/sba-loan-fraud-jeff-grant-white-collar-week-crime-bill-baroni-20201018.html

Forbes: As Law Enforcement Pursues SBA/PPP Loan Fraud, A Story Of Redemption, by Kelly Phillips Erb, July 2020: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2020/07/14/as-law-enforcement-pursues-sba-loan-fraud-jeff-grant-talks-redemption/#7a4f70cc4483

Entrepreneur’s #4 Most Viewed Article of 2020: I Went to Prison for S.B.A. Loan Fraud: 7 Things to Know When Taking COVID-19 Relief Money: by Jeff Grant, April 2020: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/350337

Greenwich Magazine: The Redemption of Jeff Grant, by Tim Dumas, March 2018: https://greenwichmag.com/features/the-redemption-of-jeff-grant

Bobbi’s Takeaways I hope that you enjoyed that conversation. Here are my 3 insights for thriving:

1. Have some ritual that centers you everyday. Jeff talked about feeling 1% off when he wakes up which is why he goes to an AA meeting every day. I’d never thought about it quite that way, but recently I started a guided meditation practice. If you’ve listened to the podcast, you know that this is something that has felt like a struggle for me. But, I founded a 12 minute guided meditation where I can move around and do stretches, etc. but it is focused on calming the mind and really feeling movement. A few weeks ago, I started doing this every morning upon rising. It’s been super valuable. This past weekend, for some reason, I skipped both Saturday and Sunday and I noticed that today I wasn’t feeling quite as grounded and centered. So, I did my meditation today and things feel more centered. When Jeffrey said that the 1% mis-alignment wasn’t bad but if you let it go on and on pretty soon, you are way out of alignment and not centered at all. It was a good reminder that having a routine that helps me be centered everyday is a great practice.

2. If you are going through something challenging, it is helpful to have a team of people around you who have been there and who understands where you are now.

3. Embrace healthy conflict as Jeff calls it. To me this means being willing to discuss the undiscussable, and to have the courage to bring up things EARLY, before they become a crisis and while they are still small enough to deal with. On an earlier episode, Josh Freidman used the analogy of dealing with things while the train is still in the station – not once it’s worked up a full head of steam.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Journal of Failure, Vol. 3, By Fellow Traveler Jeff Krantz

Jeff Krantz is a member of our White Collar Support Group that meets online on Zoom on Monday evenings.

_________________________

Reprinted from substack.com, March 29, 2022

Slow Roll

Reflections on a recent trip to the MoMA

This is how I planned for it to begin.

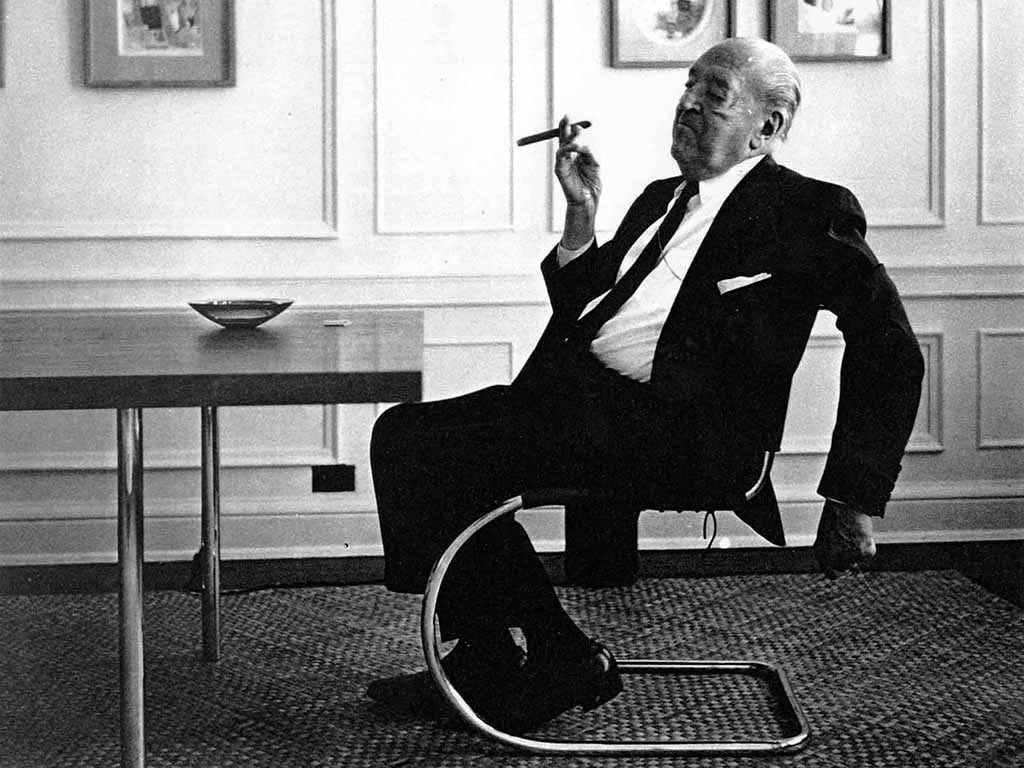

Corpulent as he was, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, otherwise held fast to his most famous adage of less being more.

Paunchier than he was corpulent, Mies seemed determined to deprive me of a pretty good opening sentence. Such is the way of things when what you want and what is true refuse to jibe.

In either event here’s the rest of the thought:

In contrast to the high priest of modernism’s guiding principle, the current keepers of the movement’s most prominent shrine, the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, have determined to take a more maximalist view of things, keeping their less than gimlet-eyed view, focused squarely on the latter half of the clichéd but still cogent maxim, by expanding the museum into every available inch of the north side of West 53rd Street, that their endowment, their trustees’ wallets, and the city’s zoning laws would allow. Mies, I suspect, has been doing a slow roll in his understated grave ever since.

It had all begun well enough, when the small cabal of wealthy, industrialist’s wives with aspirations towards posterity; determined, in the late 1920s, to erect a museum dedicated to the housing of their growing collection of modern art, called upon Edward Durell Stone to design the original building. Taking up less than a quarter of a block, that was otherwise filled with brownstones; the white unadorned, marble and glass, facade was a pleasing and clear enough statement of intent to set expectations for the radical nature of the work to be found within. Nearly a hundred years later, while still visible; the Stone building has been couched within the expansionist ambitions of subsequent museum leadership, to such an extent that it can now be easily missed by anyone on their way to the main entrance or to Uniqlo, depending upon which direction one is traveling.

With a free afternoon and an as of yet expired membership, I walked up Fifth Avenue to visit the reopened institution and acquaint myself with the newly designed museum and re-curated collection.

The original Edward Durell Stone Building, 1939.

Upon passing through the new airport-style security entrance, I was carried unceremoniously to the fourth floor by the still cramped escalators where I negotiated my way through the artwork of the latter half of the 20th century. As a result of the fully rejiggered arrangement of the heretofore reliably staid collection, I was left disoriented in a space that had long since been comforting in its familiarity. In an attempt to regain my bearings, I sought refuge among the Rothkos and a particularly fine Krasner. Unfortunately, I wasn’t left feeling any steadier.

There is a newly acquired funhouse quality to the galleries. The effect is the result of art being hung in a manner where one painting appears to be reflected back upon itself in the form of another painting from an entirely different era bearing a visual relationship to the older work; and which is hung in opposition to it, causing your eyes to reverberate jarringly between the two. The effect can leave one standing in the middle of the gallery immobilized inside of an eye rattling, dissonance-inducing loop

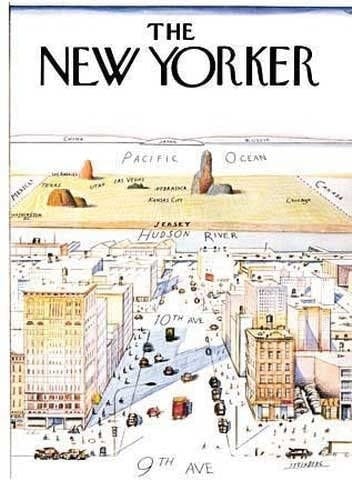

The disorienting juxtapositions are exacerbated by the physical nature of the expansion itself. Having expanded the gallery space 50,000 square feet since the last growth spurt, which itself grew the available exhibition space by nearly 40,000 square feet. The scale of the museum can now leave one feeling that the artwork extends off into a far-away horizon. Having walked a distance that felt perilously close to exercise, I thought that I might have landed inside an old Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover, wondering if I was going to exit on the shores of the Hudson or possibly somewhere in California.